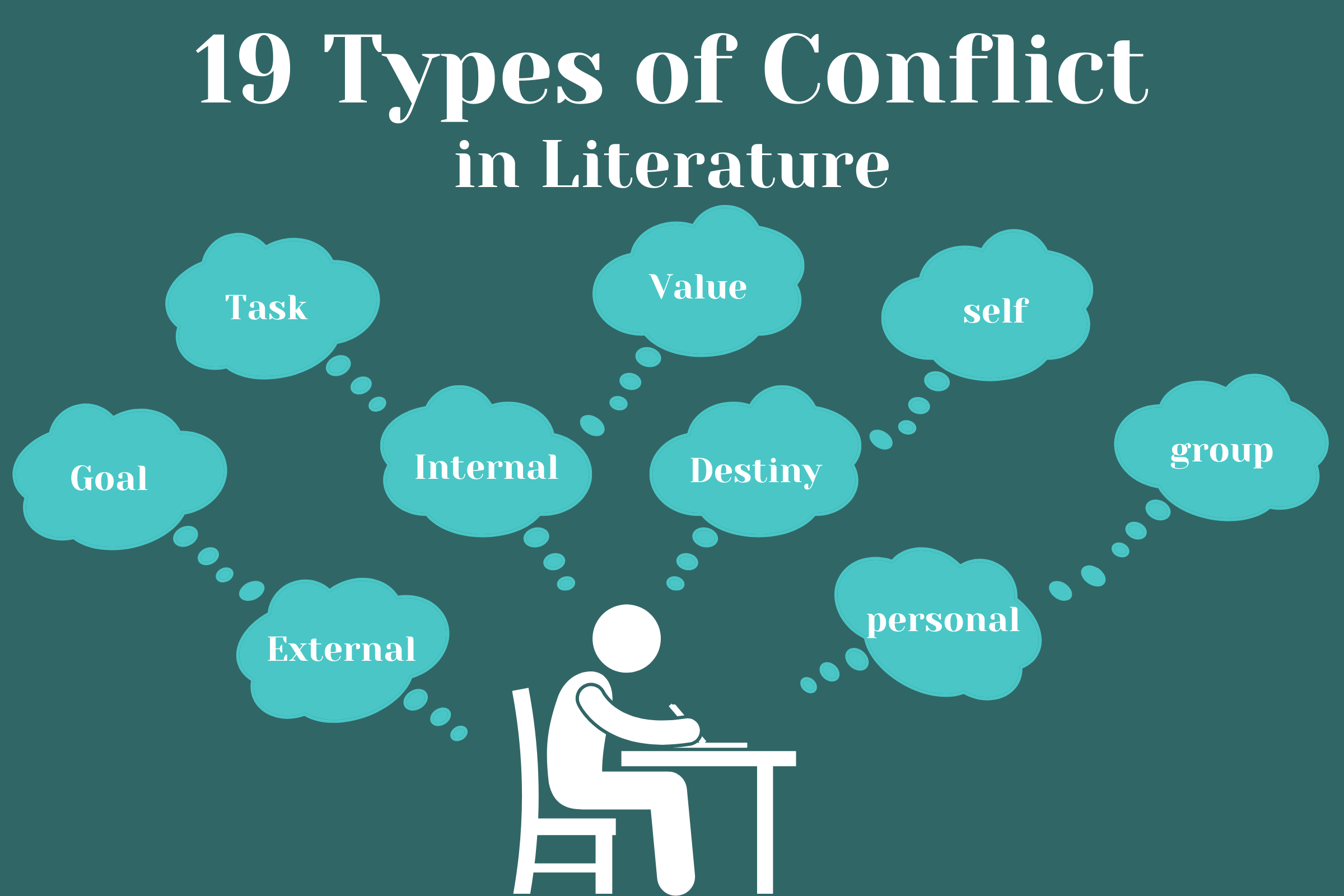

Conflict is the meat of every story, the thing that keeps readers turning that page. Whether you’re writing a short story or a grand tale of epic proportions, you don’t have a story without conflict.

Here we will focus on 1 of the 19 types of conflict: specifically internal conflict.

One of the advantages that written narrative has over other mediums such as film or television is the ability to convey internal conflict.

We all know that 9 times out of 10 the book is better, and that’s often because we get more detail and a greater understanding of how the characters are feeling. Here we will explore some different ways in which we can leverage that advantage in books and written stories, and hopefully, 1 or 2 of them will help.

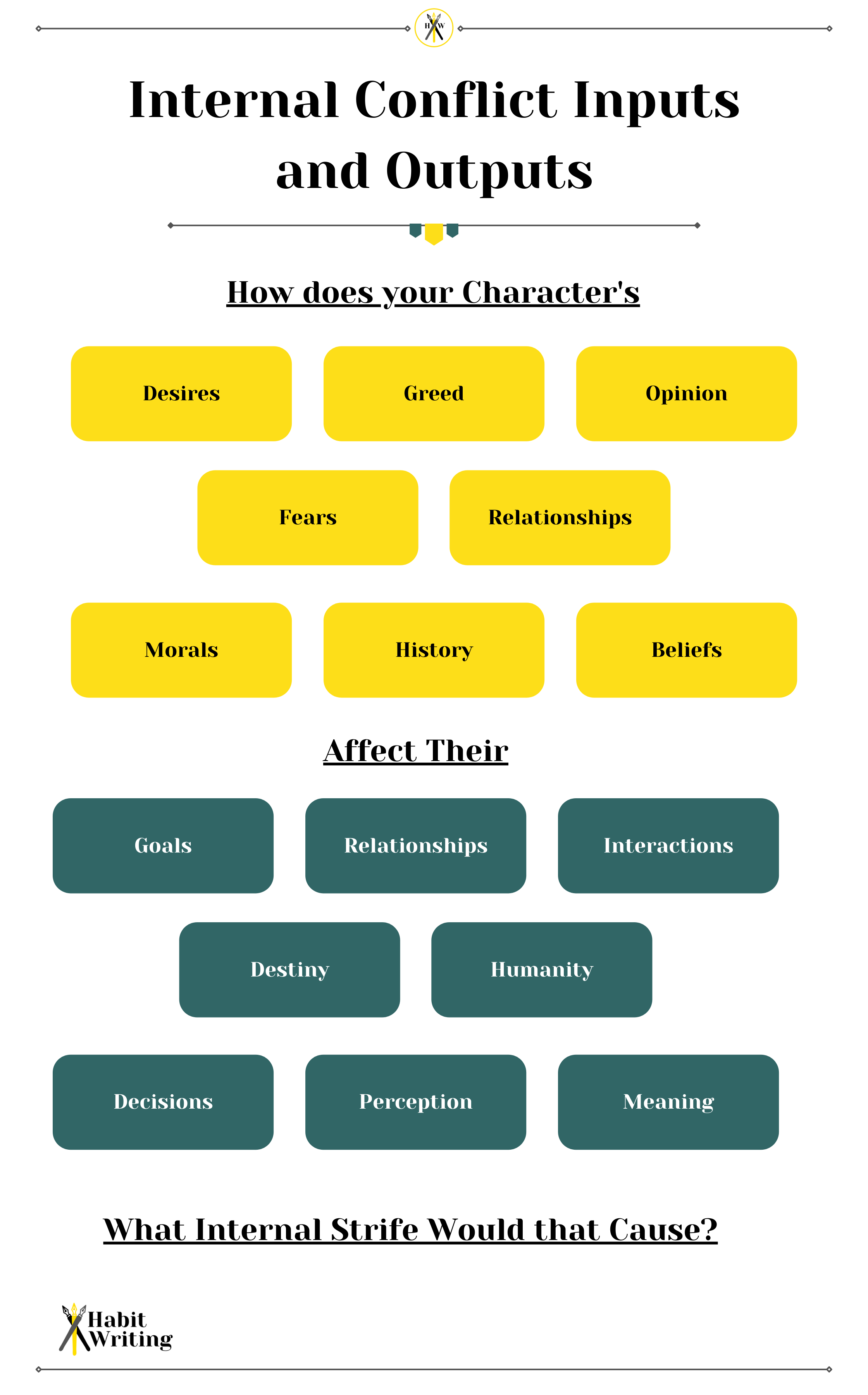

Consider Inputs and Outputs

Sometimes it’s most helpful to think about the root source of conflict. And a simple way to visualize that is by considering inputs and outputs. For example, If the input of conflict is your hero’s internal desires, and the output of those desires affects their life goals, you can structure that like so:

ask yourself, What internal desires would be problematic for this character’s goals and why?

Here is a little infographic to help get that brainstorm going.

Try writing down various inputs and outputs and write down how those might lead to internal conflict or negative outcomes for the character.

Consider that not every outcome has to be negative. It’s not a bad thing to have an internal conflict that yields positive results for the character. In fact, it makes the internal conflict more interesting and believable. Consider what positive results it would yield for the character while yielding negative results for others

Quantify It

This one may seem counter-intuitive, but sometimes numbers and lists are the best way to keep our brains on track. When trying to craft internal conflicts, consider how many each character faces. For example, try applying two external conflicts and two internal conflicts to your main character. Keep track of what they are and how they will change and evolve during the story.

If your character has an internal struggle with disliking their own powers, then maybe consider adding a moral conflict in the mix. Or find two things in their character that they need to give up but don’t want to. Try to keep to a couple of main inner conflicts for each character and take note of them so you can refer back to what they might be experiencing internally whether that be greed, fear, shame, or desire.

Our 84-page book planner and 111 day writing course.

Begin with Motivation

This one may seem obvious but it is super critical to developing internal and external conflict. For example, in Avatar the Last Airbender, Aang’s destiny is to stop the Firelord and restore balance. But a strong moral that Aang holds is that killing is wrong in every circumstance. So Aang is confronted with opposite motivations. He wants to fulfill his destiny and save the world, but he also wants to do it in a non-violent manner. Motivation is where internal conflict is born.

The inner struggle of your protagonist stems from what they want. So ask yourself what they want and why they can’t have it. Lean into the emotion of the tension that results from that and continue forward. Then consider what unforeseen consequences come from what your character does. The “Yes But”, “No And” Strategy is highly effective when planning effects of conflict.

Blend Archetypes

Archetypes are common themes, characters, plot lines, or other elements of a story that show up in many stories. A reader can often pick up on these archetypes and piece them together. But a good way to create some interesting conflict and perspectives is to blend these archetypes.

For example, the loyal sidekick is a common archetype. they often have an unyielding belief in the protagonist, they have the most stable friendship or relationship with the main character, and are often the best source of advice when the hero has a dilemma.

Think Samwise from Lord of the Rings, Chewbacca from Star Wars, or Coach Beard from Ted Lasso. These characters are often the best at supporting the main character and keep them on the right path.

But to create some inner tension and suspense, consider taking that character out of the context of their archetype. How would the loyal best friend be faced with needing to become the villain or the hero of the story? What discomfort would they feel from a sudden change to that role, and what would be the main personal consequence of that change? How would this change affect the character’s mind?

Keep in mind that you cannot escape these archetypes. They are around because they work well as story devices. But try to come up with an interesting character arc where the archetypal role they are placed in gets switched around.

Begin with a Wider Scope

Often, an internal conflict begins, not within a character, but with the social context that they find themselves in.

A princess may feel she has a duty to her people, but she is in conflict with herself because she doesn’t want to rule. A general may be commissioned to conquer, but feels guilty for doing so. A doctor may want to do no harm, but the person she is operating on is a warlord who caused the death of her parents, and unspeakable violence.

When trying to figure out what kind of inner turmoil your character is in, consider what their nation, community, family, or friends expect from them. Perhaps even take into consideration what their enemy would expect from them. This can give them contradictory intentions and lead to some really interesting stories.

Develop a Worst-Case Character for Your External Conflict

What if your hero is controlled by the villain?

Sometimes the external conflicts may come to you more readily and easily. Your story may begin with the thought that you want to write about an intergalactic trade war or a romance set in Victorian society. If that is the case, and you want to spice up your story and give better character development, consider adding flaws or attributes to your character that make them a worst-case scenario for the situation.

In the case of the intergalactic trade war, if your character is morally opposed to lying, then they may be the worst ones to go and make the deals. As for Victorian romance, if your character holds contempt towards high society, it would be challenging for them to fall for someone who believes in propriety.

Some other things to consider is what kind of fears would hinder your hero? Or what elements of mental illness might get in the way of the tasks that they are meant to resolve. The elements of inner conflict you include will add depth to your story and make for some really satisfying conflict resolution.

Consider Your Own Internal Conflicts

As human beings, we are nearly constantly in conflict with our own self. We want to live better, but not go to the gym. We want to write more, but we also want to sit on the couch for the rest of the afternoon. And beyond these superfluous examples, the deep tensions about our self-worth or purpose, about our destiny, our meaning in life, our career, or about our relationships are some of the best ideas for inspiring our writing.

What better way to explore these ideas than in the characters we put on the page. The raw and meaningful feelings that we have can become our absolute best tools in creating fascinating stories and wonderful worlds and characters.

The Problems We Have with Ourselves

In summary, internal conflicts are problems we have with ourselves. Including these elements in your story can make the characters more vibrant, the story more intriguing, and the events and motivations more believable.

Looking for more story inspiration? Check out these 7 unique magic system ideas to expand your current wonderous world. Or learn about the difference between Hard Magic and Soft Magic.

Reed Smith

Reed is the founder and builder of Habit Writing and enjoys all things writing. He loves learning about the craft of storytelling, writing messy drafts, and playing board games with his wife, friends, and family.

Our 84-page book planner and 111 day writing course.