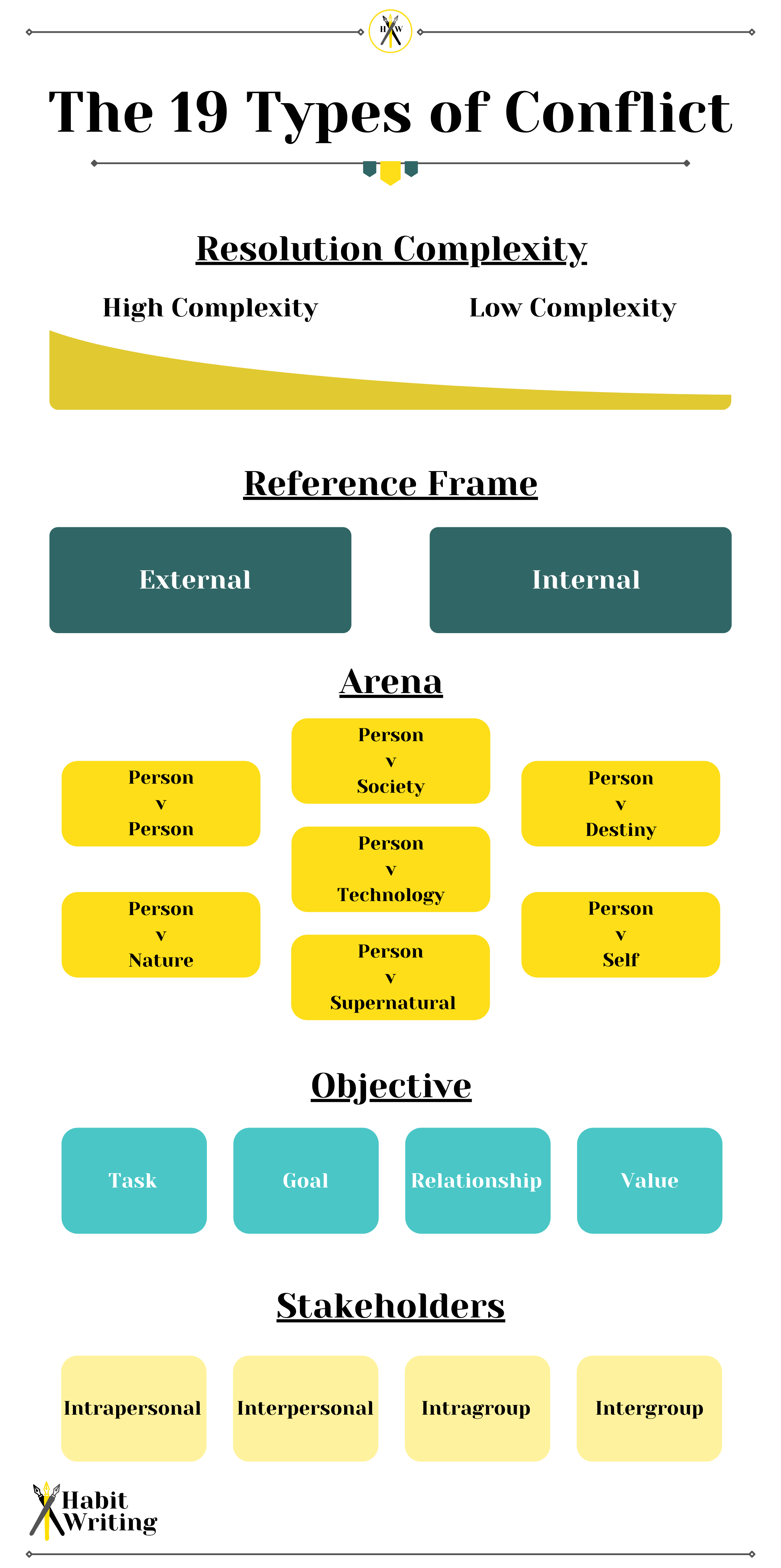

There are many ways in which conflict can be broken down and analyzed but here we have determined 19 different distinctions that can be useful when trying to consider conflict in the context of a story.

Table of Contents

First, we will divide our comparison into 5 different forms of analysis then get into the different types of conflict:

Resolution Complexity: How difficult is it to resolve the conflict?

Reference Frame: Is the conflict coming from within a character or outside themselves?

Arena: Who or what is thwarting efforts to resolve or manage the conflict?

Objective: What is the substance of the conflict?

Stake Holders: Who is involved and how many people are interested in the conflict’s outcome?

Resolution Complexity

How hard is it to solve?

As previously mentioned, this stage evaluates how tough it is to reach the end of a conflict. This is more of a range rather than two separate options. Deciding whether the conflict will be highly complex or relatively simple will help you know what your characters are working toward and what kind of challenges you can throw their way.

Let’s play with some examples. We have three conflicts in a story about Giulia. First, she wants dinner. Second, she just had a fight with her brother. Third, she is the chosen one and the only one that can save the world. Which one of those would you say is most complex?

As a seasoned writer, you would probably say “it depends,” and you’d be right. Perhaps she is the chosen one, but suppose all she needs to do is say some magic words once a day and the world is fine. Perhaps her relationship with her brother is a continuous minefield of misunderstandings. To top things off, say Giulia wants dinner while stranded on a planet devoid of life.

Those examples illustrate that complexity can vary greatly depending on the circumstances of the story. When crafting conflicts for your protagonist, secondary, or tertiary character, consider how complex their problems are and how hard it would be for them to find a resolution.

High Complexity Conflicts

These conflicts are often fewer in number and are the main driving factors of a story. Generally, the major conflict of a story is a highly complex problem that requires a lot of effort to overcome. In a story, the greater the effort and struggle, the more satisfying or heartwrenching the resolution.

Sometimes greater conflicts, such as social inequity, or bigotry are not solvable within the story, but a resolution can come in other ways. Society as a whole may not change, but a key character might, and that can make all the difference. Sometimes what changes is a character, rather than your world.

Low Complexity Conflicts

Low Complexity Conflicts will often be pertinent within a single scene or chapter. They often work as complicating factors to the larger more complex story conflicts. However, this is not always the case. Sometimes simple conflicts can grow into large conflicts. Or, at times, problems are only perceived as simple problems.

Explore how the complexity of a situation affects your scene and make sure that there is sufficient balance between complex tasks, and simple tasks and how your characters work with each of them.

Reference Frame

Where is the conflict coming from?

The opposing twins, external conflict, and internal conflict are some of the most talked about. The forces involved can be a number of things, which we will get more into when we explore the Arena level of conflict.

In literature, it is important to actually break some of the barriers that are often put up between these two. An external conflict is only interesting if a character cares about it. And internal conflicts are made all the more tantalizing when it is halting the progress of external conflicts. These two often interact in the narrative, and they build and feed off of each other.

External Conflict

An external conflict is one that pits an individual or group against an external force. The simplest example is an antagonist, someone actively trying to stop your main character or group of heroes. Conflict resolution is usually achieved through some sort of vanquishing of the opposing force in some way, though that is not always the case.

Internal Conflict

An internal conflict happens within a character. A great example is the conflict between what a character wants and what they actually need. This inner conflict often contextualizes the events happening around the character through emotion. Consider how thoughts and opinions may contradict within a character to create self-conflict, this will help immerse your readers in the emotion of the story.

Our 84-page book planner and 111 day writing course.

Arena

Who is involved?

This is exactly what it sounds like. If the conflict is the battleground, then who or what is standing on the other side of the arena? Every power struggle has multiple sides vying for victory, whether that be a millennia-long war or a simple disagreement about where to set the thermostat.

These are broken down into 5 which are external and 2 which are internal.

External Arena

Person vs. Person

This one serves as the basis for many literary conflicts. Person vs. person is simply a person against another person. People don’t get along, and sometimes in fantasy and sci-fi, they don’t get along and can destroy worlds or something. The scope can range but dramatic tension does not scale perfectly with scope.

Perhaps characters find themselves on opposite sides of an intergalactic conflict or perhaps they both want to go with Sarah to prom. Some stories can make the intergalactic conflict rather dry, and others really sink their teeth into you because Sarai should obviously go with Treyvon rather than Ricardo. It’s also important to point out that “person” refers to sentient beings.

Person vs Nature

This conflict lies between the individual and nature. The most obvious example of a natural conflict is disaster movies. The humans want to not die, and the mega earthquake shark-infested firestorm is making that a rather difficult goal. Likewise avoiding dangerous animals (whether caught in a tornado or not, looking at you sharky boys.) is a classic example of person vs. nature. Some other good ones are survival stories against the elements or stories about summiting mountains.

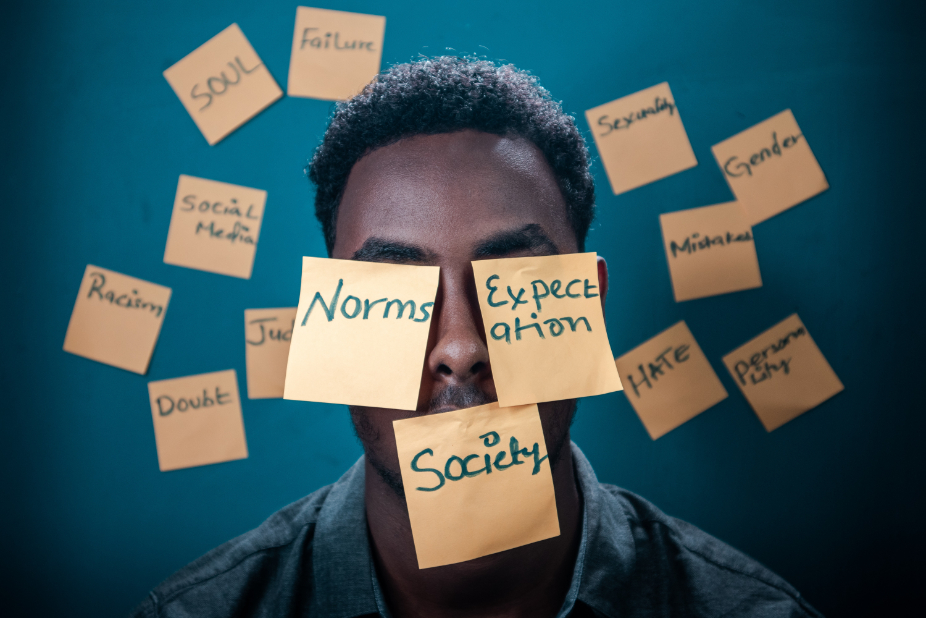

Person vs Society

If your character is fighting against the forces of societal norms, that’s person vs society. An easy example is Hunger Games and the many dystopian stories like it. But there are deeper stories of this kind of conflict such as The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas. Great conflict and pain in our life come from racism, ageism, ableism, audism, and many other forms of social stratification.

These deeper stories should be explored and told. Norms like these are often deeply pervasive and are not resolvable over the course of a story but are resisted in a meaningful way. Be sure to be sensitive to your readers in the way that you portray these deeper conflicts; make sure that your story feels true to real-life experience if you choose to include these topics in your story.

Person vs Technology

The classic Sci-Fi idea. “We built the robots, but they were too smart, and now they want to kill us and have german accents.” But it may also be about how technology changes the world and how we interact with it. Think terminator, but also think job loss due to automation. We will leave the whole “can machines achieve sentience” debate for a different blog post.

Person vs. Supernatural

This one is a fun one for us fantasy fans out there. While sometimes the magical forces that face the characters are simply sentient beings and would therefore be person vs person, if your character is fighting a curse or a spell, that is a classic person vs. supernatural conflict. Or if the magic your character depends on suddenly stops working, then that is an interesting idea that Brandon Sanderson has explored many times.

Internal Arena

Person vs. Self

This is when a character is in some way against themselves. This can be as subtle as disliking one’s occupation or as deep as a soldier considering the meaning of life and his own ability to take a life. This one is almost always included in every piece of literature somehow. We are self-contradictory beings and that makes this type of conflict both engaging and relatable.

Person vs. Destiny

While one could argue that destiny is an external force, and it is sometimes portrayed as such, the conflict related to destiny happens internally. A destiny, fate, or mission is only as powerful as the character allows it to be. What matters is how much the character believes in their own destiny and whether or not they are taking steps to try to live up to it.

Objective

What is the source of conflict?

The objective is the meat of the conflict. What is the driving reason for the given conflict and how does it contextualize the situation? It is important to note that these can fill in the meaning of any of the seven arena-level conflict types. Keep in mind all of these are heavily interrelated.

Task Conflict

A task conflict is often the simplest of the objectives. Someone is taking actions and the conflict arises when forces oppose those actions. These actions may be opposing despite the two groups having the same goal. Actions can be different and opposite, even if goals are similar. The classic, if we fight back with war crimes then we are no different than the bad guys trope is an example. Sometimes conflict is derived from two people trying to complete the task. This one differs from Goal conflicts in that it is strictly action-based but the two are very intertwined.

Goal Conflict

Opposing goals breed conflict. If the goal is to get the One Ring to the fires of Mount Doom, the conflict the Fellowship faces is derived from the evil forces of Sauron trying to actively hinder that goal because they have different goals. Or at times having the same goal or incorrect goals leads to conflict. Two musicians wanting the first chair in the performance or wanting to run away even though the protagonist is the chosen one.

Relationship Conflict

This one is derived from some kind of history between two characters but deals more on the emotional level than the others. This can be a self-conflict of wanting to be a better daughter, a workplace conflict because of a fiery personality clash, or just really wanting to be friends with the popular kids. The obvious example is Romantic tension and the infamous love triangle. As human beings relationships matter deeply to us, and when relationships have tension in a story, that provides some really relatable literary conflict.

Value Conflict

If your character values are different from what another character values, that leads to conflict. This is often an exploration of morality. The Avengers essentially had a value conflict in Civil War. Stark wanted to avoid catastrophe and wanted to keep the team together because that is what he valued. Rogers wanted to avoid oversight and the kind of threat that may come from a similar situation to Hydra infesting S.H.I.E.L.D’s organization. Beyond what your characters are doing, what they want to do, and who they care about, consider what your characters value (think D&D alignment). Try to include characters with different values to make your cast feel more alive.

Stakeholders

Who cares?

This conflict analysis overlaps with the others but can yield some important insights as you structure your character conflict and try out different conflict styles. Analyze what the resolution of the conflict is, and who is involved in the conflict, then consider who cares about the outcome of the conflict. The best way to use this type of conflict is to list the characters that would be rooting for one side or the other.

Intrapersonal Conflict

This is the internal personal conflict. However, in this analysis, we will look at how this kind of conflict situation involves others. The arena is person vs. self, but consider who would be in the stands rooting for one side or the other. If your protagonist is struggling with depression, her companions would have a stake in the outcome. They would take steps to encourage and uplift your main character. Consider how each of them may react to the conflict, or whether the main character would want people to react to their inner conflict.

Interpersonal Conflict

The arena for this one is person vs. person, but in the stands are all those who are hoping for some kind of resolution. If you have two heroes fighting, the baddies would want them to kill each other, while the other heroes would push for peace and understanding. The conflict can only be resolved by the two people involved, but there are others who want to influence the results in some other way.

Intragroup Conflict

This one is often used when you have an ensemble cast. This is a conflict from within a group and usually ends with some kind of factional division. This can derive from any of the objective-level conflicts. Again consider the people who care that are outside of the group and how they may try to influence the resolution.

Intergroup Conflict

This one comes after the fictional division. This kind of group conflict can be large or small. The fun begins as you contemplate how each of the individuals would react to the conflict based on their values, relationships, and goals.

How to Create Conflict in Your Story

Have we said “conflict” enough? Whether dealing with an organizational conflict, an interplanetary conquest, or a romantic fling, conflict is the meat of a story. Consider how many conflicts to include and who will be involved. Consider what different personality types are involved in a conflict and who cares about the resolution. Examine how different people would approach conflict management. Then consider these ways in which we analyzed conflict and how that can help you build depth into the story.

For more help with your story check out these ideas for creating magic systems or learn about hard magic vs soft magic. We look forward to hearing your thoughts in the comments below.

Reed Smith

Reed is the founder and builder of Habit Writing and enjoys all things writing. He loves learning about the craft of storytelling, writing messy drafts, and playing board games with his wife, friends, and family.

Our 84-page book planner and 111 day writing course.